Charles "Bob" Hogg relaxes on the living room sofa of hist split-level home in Munhall, adjusts his wire-rim glasses and smiles.

The 70-year-old's brown eyes shine as he speaks proudly of his community, his family, his church, his country. But as he prepares to talk about his trip to Europe next week, he changes. The World War II veteran shakes his head sadly and says "We were butchers".

On Dec. 16, Hogg will be in Bastogne, Belgium, to participate in the 50th anniversary of the Battle of the Bulge, the six-week Allied struggle against the last of the best German forces in Europe. He knows he'll have to relive the horror he saw as a young man. But he'll also remember the simple facts of humanity he found amid the death and destruction of war.

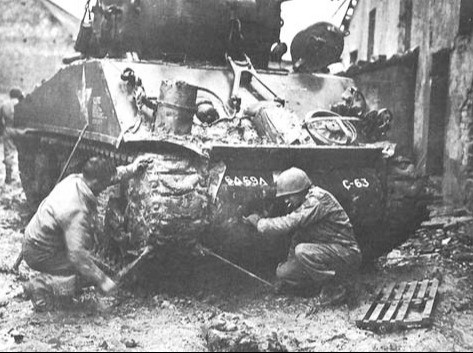

Now a retired U.S. Steel account supervisor, Hogg was then a 20-year-old light tank gunner with the 69th Tank Battalion of the 6th Armored Division of Patton's 3rd Army. He was in the thick of the fighting that irrevocably pushed the Germans back into the Fatherland.

Fought from mid-December 1944 to the end of January 1945, this biggest and bloodiest battle of the war in western Europe claimed 180,000 casualties, including 10,276 Americans killed, 47,493 wounded and 23,218 missing. Hogg watched comrades die and wrought destruction on an enemy for whom he admits he had no animosity.

"The Germans where just doing their duty, and they did it very well," he said. "The regular soldiers were doing the same thing we were. They were defending their country."

Hogg's unit was fighting in the Saarland and was about to push for the Rhine River when the German offensive that became known as the Bulge started on Dec. 16. He spent Christmas passing through Metz and New Year's Eve in this first Bulge engagement in the village of Neffe just outside Bastogne.

"Before you enter battle you are really scared," he remembered. "But once the battle starts, you are too busy. There's no fear then."

No fear, just horror.

"My tank was moving into Neffe and there in the road were buddies from another unit I had trained with stateside -- already dead and gone. Tanks had run over them. The Germans had captured a tank from 3rd Armored Division and were using it against us.

During the first days of January, Hogg fought in the farm fields and villages along the Bastogne perimeter. In the coldest weather recorded to that time, the 6th Armored Division helped repulse parts of eight German divisions in fighting at Neffe, Mageret, Longvilly, Bizory, and Arloncourt. Hogg was at Neffe.

"To cool our tank engines, air was drawn in through the fighting compartiment," he said. "When it's 10 above zero and thos fans are turned on... My God, talk about cold. My gunsight was covered with ice. All I could do was stick my head out the turret, fire my machine gun, and hope I hit the enemy."

The peak of the German offensive was Jan. 3 and 4. The Germans attacked repeatedly day and night.

"At night, the whole horizon lit up and artillery came down like fire rain," Hogg pauses with the memory. "The sky blows up with noise and as the artillery lifts, the German infantry is on you screaming and hollering... Oh Lord!."

After the tide turned, Hogg's unit participated in the push across the Rhine. Hogg described images of carnage --- the American tanks coming upon a German platoon trying to dig in an open field. That was a slaughter, he said. A lone German soldier trying to hit a U.S. tank with a Panzerfaust, an anti-tank weapon similar to a bazooka. The soldier was torn to bits by tank machine-gun fire.

The worst day for Hogg was shortly after crossing the Rhine at Worms. The Germans concentrated direct fire from 88mm guns on the advancing armored forces accross the river. Of Hogg's 15-tank unit of 60 men, 20 men were killed or wounded. At Giessen, Hogg's unit watched as U.S. 1st Army troops pushed German soldiers through the town.

"We were butchers. If we received any civilian resistance going into a German town, our orders were to shoot to kill anything that moved, even children. After we learned of [Germans SS troops] killing American prisoners, well, we had boys who didn't take German prisoners."

Hogg recalled other images, of selfless humanity in the most inhuman conditions. He spoke of Mike Skavinsky, a cook from Lawrenceville who volunteered for tank service.

"At daylight, Mike got out of his tank and went to the wounded Germans. They had blankets in their back packs and Mike would be out there in the bitter cold and deep snow covering those guys with their blankets. At night he was shooting at them. In the morning he was trying to save them."

Mike Skavinsky was killed on the last day of the war.

Hogg was wounded in Kaisershuten when his tank was hit by a high explosive shell from about 25 yards. He was taken to a field hospital in an ambulance with an American first lieutenant and a German major who had wounded each other when they came around the side of a building at the same time.

"The German was worse off," Hogg said. "During the ride, the first lieutenant and I, we'd hold his stretcher out the door for him so he could relieve himself."

There were times that Hogg said he didn't bathe for weeks or was covered head to toe with lice. When K rations were frozen solid, he said he ate crackers crumbled in water from ice melted on the small Coleman stove in the tank turret. "It was so cold, I cursed my mother for having me. We hadn't gotten our winter uniforms or coats or boots yet. But we took turns getting out of the tank to get ice." Hogg said. "One time, the assistant driver didn't want to do his turn. We egged him on and he finally got out. A shell exploded nearby and killed him." "You lose guys in wat," he says softly, his eyes dimming. "At the time it hits you hard. You almost lose your religion. Why does God let so many good men get killed if he cares about every bird?

Hogg said his father was gassed and wounded twice in World War I. After returning home, he never again attended church. But Hogg didn't lose his faith like his father. If anything his faith has strengthened. A Lutheran who married his former high school sweetheart, Agned Patterson, two years after the death of his first wife, he now attends services twice a week: Sunday morning at Lutheran Church and Saturday night Mass with his Catholic wife.

He also hasn't lost his faith in humanity. It was a mutual memory of shared kindness on a cold night during the fighting at Neffe that accounts for Hogg's invitation to be in Bastogne next week. At Neffe his tank was parked across the road from an old stone farm house partially destroyed by artillery. To get out of the cold, he and his tank mates sought shelter in the house, making their way into the cellar. There they found a man and women sitting between piles of coal and potatoes, with a terrified boy huddled in his mothers arms. Thankful that the soldiers were Americans, they welcomed Hogg and his mates into their sanctuary.

Thirty years later, in 1974, Hogg and his first wife Betty, went to Europe for their 20th wedding anniversary. Hogg wanted to tour the areas where he had fought, but he wasn't prepared for the intensity of the emotions that gripped him as he drove down the road into Neffe.

"As soon as I saw the sign to Neffe, it all came back -- what all those boys did, what we did. I cried all night."

The next day, he found the old stone farm house where he and his tank mates had hidden. In the yard was a man staring at the rented German car Hogg was driving. Hogg struck upon a conversation with the farmer and told him about the night he had spent in the basement with a man, woman and a little boy.

"The man started yelling and ran for the house," he said. "A minute later, he was back with his wife and children."

The man, today a wealthy Belgian farmer and town alderman, was the little boy who had spent that cold night in his mother's arms. Gilber Stilmant remembered the Americans, and Hogg has maintained friendly correspondence with him ever since. Hogg will be at Bastogne on Dec. 16 at Stilmant's invitation.

Hogg didn't plan to go, recalling his 1974 visit and the pain of remembering what had happened there. But his daughter, Amy, convinced him this was his chance to pay tribute to all who fought and died in the Battle of the Bulge. German veterans are also expected to attend.

"War is horrible, but we all just did our duty. As the years go by, the memories dim. You're working, you have a wife and kids. It starts to recede, but never entirely. I guess I learned that if you have a good roof over your head, a good wife, good kids. ... If you just do the best you can with what you have, that's enough."