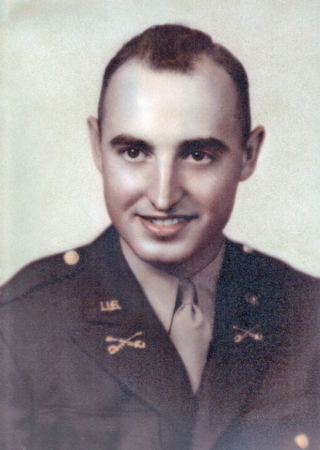

His friends outside of the military might never know that he earned the Silver Star, Bronze Star and Purple Heart. If people  ask to recognize him for his service, he’ll likely brush them off.

ask to recognize him for his service, he’ll likely brush them off.

“I don’t want to be a part of all that,” says Shockey, who moved to Shawnee in 2004.

But Shockey, 94, certainly had a significant record of service, serving as an aide-de-camp to a two-star general under Gen. George Patton during World War II and going on to serve in Korea and teach at four military schools after making a career in the military.

Shockey grew up in Elkhart, Ill., working his way through college during the Depression and going on to teach high school for three years. Then, at the age of 27, he was drafted into the Army. It was June 1941, six months before the attack on Pearl Harbor, so all eligible males were drafted for one year of service.

Shockey attended armory school, trained to be a tanker, and was assigned to an armored division in Camp Polk, La. He was on an “R&R” weekend in Beaumont, Texas, the day of the Pearl Harbor attack.

“That one year (of service) was changed to ‘the duration of the war,’” he said. “… I was counting off the months, thinking in six months, I’d be back home again.”

Once he knew it would be some time before he left the Army, he decided he wanted to become an officer and applied and was accepted to the Officer’s Candidate School in Fort Knox, Ky. He became a 2nd lieutenant and was then assigned to 6th Armored Division, sent to train for seven months in the Mojave Desert, believing they would be sent to Africa.

But in the end, the division was sent to England in January 1944, training for the D-Day invasion. But before arriving in England, Shockey was informed that Maj. Gen. Robert Grow, commander of his division, was looking for two officers to become aides-de-camp, basically assistants. Though he was surprised at the request — he said until then, he’d never even seen a general — Shockey was selected to be the senior aide.

“My job, rather than riding around with a tank all the time, I rode around with the general,” Shockey said. “Wherever the general went, myself and my subordinate aide would go with him.”

Though Shockey admits he didn’t necessarily want the job at first, he felt he could not turn it down.

“Not many people have the opportunity to do a job like this,” he said. “It sounds rather simple, but it’s not. The biggest thing that was wrong as far as my situation, if the general decided to relieve an officer, he’d use you temporarily to take command and do something.”

Shockey’s responsibility also was to protect Grow, ensure that he survived, so he was always on security detail. Which meant he was often in the same room as Grow’s superior, Gen. Patton.

“I never did get to shake his hand,” Shockey said of Patton. “… Every time he showed up, I ended up getting something that wasn’t very pleasant to do.”

But he had plenty of time to observe greats around him, developing a great admiration for both Patton and Grow.

“My observations about generals are that most are intelligent, ambitious, crave publicity if favorable, and hate war,” Shockey wrote in a memoir for the 6th Division. “However, it there is a war, none want to be left out of the action. General Grow was such a person.”

Shockey’s division landed on Utah Beach about six weeks after D-Day.

“I missed all the fun at the start of the thing,” he laments.

The division was headed southwest to Brest, France, but then was ordered to push to the German border. After a battle in Huelgoat, for which Shockey earned his Silver Star medal, they traveled to Nancy.

On Sept. 30, 1944, Shockey was caught in a mortar barrage that killed six others. His face was cut open and he received mortar fragments to the arm, chest and both legs. He was evacuated to England and after 10 weeks of recovery, he returned to battle, eventually making it back to his division on Dec. 15, 1944.

Shockey’s division was assigned to help in what would become the Battle of the Bulge at the Belgian town of Bastogne. It was a cold, wet winter, he remembers.

“I don’t know how I kept from freezing to death, if you want to know the truth,” he said, remembering how many men in the division came down with trench foot.

This was one of Shockey’s run-ins with Patton, who wanted Grow to determine if the Germans had begun a retreat. The cloudy weather made it impossible for reconnaissance planes to gather intelligence, so Shockey led two tanks in an attempt to get behind enemy lines — only to encounter heavy mortar fire. Luckily, the next day the weather was clear, so he didn’t have to make a second attempt.

The division eventually crossed through the Siegfried Line, the German defense system stretching more than 390 miles with more than 18,000 bunkers, tunnels and tank traps. They fought their way into central Germany, where they stayed until inactivated on Sept. 18, 1945.

Shockey decided to stay in the Army after the war and received a regular commission. He went on to teach at four different army schools, served as a secretary at the U.S. Forces headquarters in Austria, and served on the U.S. Military Armistice Commission in South Korea, among other accomplishments.

Shockey retired at the rank of colonel in 1970, and moved to Shawnee in 2004 to be closer to his daughter.

He doesn’t like to talk about heroism, because he doesn’t think he’s a hero. Asked about the meaning of freedom on days like Independence Day, he points to the answer he gave an Iowa City newspaper in a 2001 story.

“It’s just too bad that there isn’t some alternative to war that works,” he said. “There’s nothing worse than coming across a battlefield where you see maybe 100 dead bodies laying, shot down. I experienced this more than once … freedom doesn’t come cheap.”